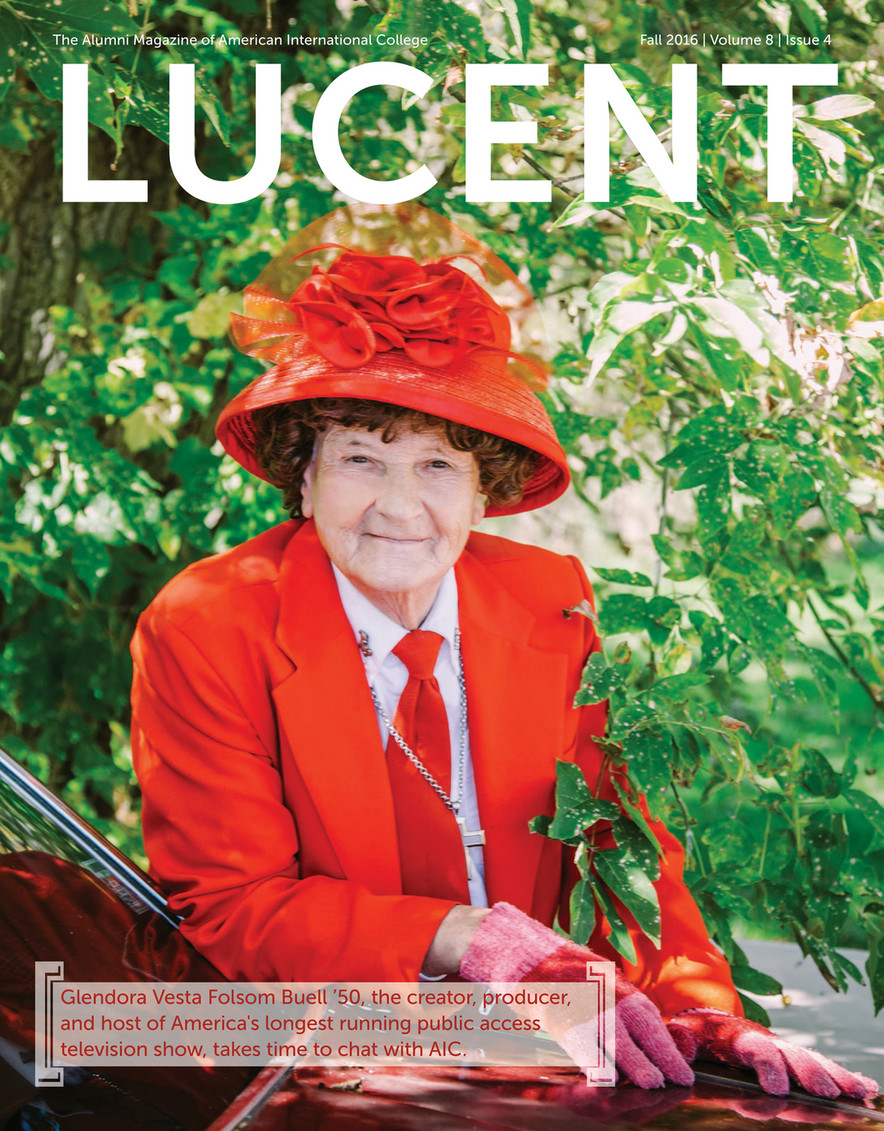

Glendora Vesta Folsom Buell ’50, the creator, producer, and host of America’s longest running public access television show, takes time to chat with AIC.

Glendora Vesta Folsom Buell ’50 is like a force of nature in a jaunty hat: singular, persistent, unstoppable.

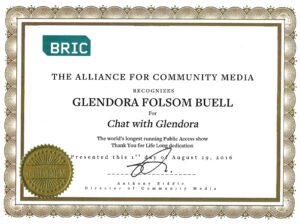

For more than six decades she has devoted herself to the work she loves as a television personality, public access TV producer, judicial activist, ethical vegan, author, philosopher, and exuberant ambassador of happiness. She is a joke-teller and a freedom fighter; a truth-speaker — especially to power — and a lifelong truth-seeker. In 2013, Glendora received the Clara Lemlich Social Activist Award in recognition of her tireless efforts to defend the public’s right to community access broadcasting free of corporate or political censorship. In August of this year, she was honored by the Alliance for Community Media for being the most prolific public access television producer with the longest-running show, A Chat With Glendora (11,300+ episodes and counting), a talk show she is still producing and hosting. At 88, Glendora continues to steer by her own lights, staying as busy, irrepressibly cheerful, and dedicated to her calling as ever.

Born May 1, 1928 in Presque Isle, ME, the fourth child of Ralph and Edna Folsom, Glendora grew up in a loving family that valued hard work and appreciated a good sense of humor. “The joke telling started with my parents. Both of them had such great personalities, this great compassion and interest in other people.”

Her sister Helene, 12 years her senior, went to Aroostook State Normal School and became a teacher. Her oldest brother, Ralph Arnold Jr., left home to work as a clerk at First National Store in Lincoln, Maine, a town 130 miles south of Presque Isle. But after the stock market crash, in the teeth of the Great Depression, Glendora’s family, like so many others, suffered financial catastrophe. “My father owned a reasonably successful chain of barbershops, but one day my parents went to the bank to get their money and the bank was closed. All of their savings was gone.”

Her father got an offer to work as a barber in Lincoln for seven dollars a week, and Glendora remembers the journey to their new home. “My parents packed up my brother Gordon and me and we left in the middle of the night. It was 40 degrees below zero practically every night, and that trip was like going across the prairie. “That was the year Parker Brothers came out with the board game Monopoly. We couldn’t afford to buy one but Lincoln was a paper mill town, and my mother took in boarders who would bring home these scraps of paper, so we made a Monopoly game out of all those scraps. It took us all winter. The only thing we bought were the dice.”

To supplement his meager wages, Glendora’s father worked several jobs, one of them selling blankets door to door on an installment plan of a dollar a week. But if someone couldn’t pay, he had to repossess the blanket — a bitter task in the bitter cold of Maine’s winters. After telling the story, Glendora simply asks, “Can you imagine having to do such a thing?”

By 1938, Glendora’s father had found work that paid better as a barber at the Bangor House and the family moved again. Glendora entered fifth grade in Bangor, ME, and her brother Gordon entered the Marines before the family moved once more in 1941 to Springfield, Massachusetts. “My father got a job in defense. I remember the Day of Infamy, being huddled around the radio. The terrible truth is the only thing that got us out of that depression was the war.”

“The young man, who went on to Yale, who put me up for class president did it as a joke, but I ended up winning. The principal was devastated that the class clown should be class president!”

On the advice of friends, Glendora’s parents enrolled her in Springfield’s Classical High School, known for its rigor and reputation for preparing graduates for the Ivy Leagues. “Here I was, this little hick from Maine. They wouldn’t even accept my Latin and made me take it over.”

But Glendora, whose idol was Bob Hope and who dreamed of a career in comedy — an iconoclastic choice for a girl in the 1940s — quickly became popular at school and was eventually nominated for president of her class. “The young man, who went on to Yale, who put me up for class president did it as a joke, but I ended up winning. The principal was devastated that the class clown should be class president!”

Thanks to an English teacher, Edmund Smith, someone who “knew how to turn a teenager into something worthwhile,” Glendora blossomed academically and earned a place on the honor roll. “By the time he got through with me, I graduated magna cum laude, but I told everyone I graduated cum lousy.”

Though Glendora had earned good grades, her SAT scores were disappointing. “I didn’t know what I was doing, and my poor English teacher was so upset.”

She went off to wait tables at the Equinox House, planning to enroll in Springfield Junior College in the fall, but a mysterious Providence intervened. “I received a letter telling me that American International College had awarded me a full scholarship. I never found out who was behind that.”

Glendora entered AIC and discovered that she was well prepared to handle a full load of classes. “Taking five subjects didn’t really fulfill my academic longings, so I took six. By the time I was a junior, I had enough credits to graduate in both psychology and English.”

Seventy years later, she can name the professors who left a lasting impression. “Dr. Wells for psychology, from Harvard School of Education. Mrs. Morse taught literature — she was a grand person. Henrietta Littlefield taught German. She was always beautifully dressed and wore these Victorian hats. Drs. Spoerl, husband and wife, were both ministers in the Unitarian Church and taught in psychology and philosophy. Isadore Cohen taught a biology course for psych majors, and Dr. Gadaire, who was extremely popular, so personable and entertaining, also taught biology. Mr. Duffey taught literature, though it may have been called Aesthetics then.”

Dr. Dorothy Spoerl chose Glendora to work as a psychology lab assistant and for a year she took attendance and graded papers and was on track to be valedictorian, but in her senior year, Glendora admits, she drifted. “I think it was adolescence. I had really done everything I could do. Heavy courses were a breeze to me. I registered for physics and mathematics, but I dropped physics, struggled with math, and started going out with the math grad assistant. I think I was looking for other excitement, but I regretted losing focus like that.”

Nevertheless, her experience as a lab assistant at AIC paved the way for her to be hired in the same capacity at UC Berkeley. “After graduation, a friend of mine who was a year ahead of me at AIC wanted to go to San Francisco, so the two of us got jobs as car hops and saved up enough money to go across the country by Greyhound Bus.”

The friend eventually ran off with a man she met in California, leaving behind a heartbroken boyfriend back in Springfield, while Glendora received an unexpected offer from Smith College to work as a lab assistant, another example of what she calls “that same benevolent Providence, somebody behind the scenes, that same beautiful spirit” that was looking out for her.

Glendora declined the offer from Smith and soon returned to Springfield, still, as she puts it, “seeking a life.” She moved to Washington, D.C. briefly, but the heat, humidity, and alarming bugs that shared the apartment she rented sent her back home again. It was at this point that Glendora sat down to seriously contemplate her future and her place in the grand scheme of things. “Certainly we are all created to do something in this world. What was it that I was created to do? The answer eventually came to me, and it was television. And that’s been the answer for 65 years. I’ve never left it. It’s like a monastic vow. I am by nature a performer, but it’s a difficult choice. You’ve got to be dedicated.”

Glendora found her way back to Hollywood thanks to Vaudevillian-turned-Broadway-performer Bobby Clark and his wife, whom she had met during her stint as a “relish girl” at the Equinox House. “The Clarks had taken a liking to me and their friend, Elsi Paris, who operated the Hollywood Bridge Club, was driving back to LA with a friend of hers and they offered me a ride.”

Glendora lived near UCLA and quickly found work on the LA Stock Exchange. “I couldn’t stand that, but one day during my long commute on the Hollywood freeway, I did see Nat King Cole in a rage at the driver in front of him.”

When Glendora spotted an ad for a course in television writing through the UCLA extension, she wasted no time signing up for it. “The class was being given in the NBC studios right there at the corner of Sunset and Vine, and across from the lecture room was the personnel office.”

“I knew I had chosen the right field, and this was my door in.”

Glendora landed a job as a script girl at NBC, running the mimeograph machine in the basement. “This was television in its infancy. The money, the creativity, the excitement. People ate TV dinners in front of it, you would hear people discussing what they saw on television the night before. I knew I had chosen the right field and this was my door in.”

Glendora made the most of her foot-in-the-door moment, running last-minute script changes upstairs to the cast of Dragnet, meeting Groucho Marx who was filming You Bet Your Life, running into Robert Young of Father Knows Best fame kicking the canteen machine. But the most exhilarating connection was with Bob Hope, her hero of humor. “I had collected four scrapbooks of him and when I showed him one, he said to his agent, ‘She has more pictures of me than you do!’ He was on the radio then at NBC, and after he finished audio taping his show, if he felt like it, he would stay and tell a few jokes for the studio audience. He let me try out my monologue in the after show, and I came floating in on the wings of Bob Hope. His favorite engineer, Johnny Pollack, would boost the audio for me so the laughter sounded twice as loud, and he recorded it for me on a platter.”

Glendora also got to know Jack Douglas, an aspiring comedian and writer for Hope. When she took a hiatus during the summer to go back east, Douglas asked if she’d do him a favor and drive the car he’d left at his summer home in Bucks County, PA back to Hollywood. Glendora agreed, and she and her mother, who came along for the ride, drove Douglas’s 1950 black Buick convertible across the country like the intrepid heroines of a madcap Hollywood movie.

Glendora continued at NBC while the Colgate Comedy Hour was going strong with the likes of Eddie Cantor, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, and Abbott and Costello. She had her comedy “platter,” a “presentation card” that the people from Dragnet had printed up for her, and professional photographs, but she knew, if she was going to make it, she needed experience. “I decided to go back to Springfield, find a small television station, and get myself in front of the camera.”

Her career as a children’s show host began in 1953 with Glendora and Her Picture Party, which aired on channel 19 in Pittsfield, MA for 15 minutes once a week. An artist from the Springfield Public Library would illustrate an incident from the life of a famous historical figure and youngsters would come on the show and tell the story as they saw it, in their own words. “I just wrote the show up, put it under my arm, and took it up to The Berkshires. And one of the first lessons I learned is to get a sponsor!”

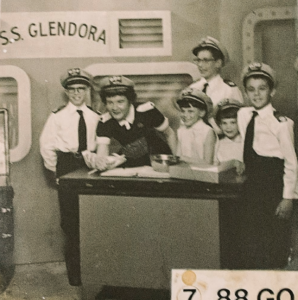

“It was charming live television, creative and educational. I always spoke to the children as though they were peers, and it had a great effect.”

Glendora soon moved to WMUR in Manchester, NH, where she launched a much more ambitious endeavor, the SS Glendora, in which she played the ship’s captain and local children would play her sailors. “The general manager loved the program and he ran the show for 45 minutes five days a week. It was charming live television, creative and educational. I always spoke to the children as though they were peers, and it had a great effect.”

In the midst of all this career building, on Christmas Day in 1954, Glendora married Franklyn Buell, a reporter for the Springfield Union, and former boyfriend of the young woman she had first traveled to California with. Franklyn would eventually become a star at the Buffalo Evening News, writing stories about “little people doing great things,” a theme that runs through both of their work. Franklyn Buell passed away in 2003 and Glendora maintains an archive museum of their respective work, including tens of thousands of pages of court documents from her judicial activism days, and every piece her husband ever wrote during his 37-year career as a journalist.

After leaving WMUR, Glendora landed at WBZ-TV, the Westinghouse station in Boston, the largest in New England. “After searching all over Massachusetts, and even up to Buffalo for sponsors, I finally went to a little one-man advertising agency in Hartford, CT, and asked if he had any sponsors for the SS Glendora. Turns out, he had one client, Milton Bradley, which also just happened to be owned by James Shea, a trustee of AIC.”

The SS Glendora now attracted the attention of some of the top newspapers in the country, including the Boston Globe, the Boston Post, and the Christian Science Monitor. “I had so many ideas and I was working so hard. My parents helped with the costumes and I wrote the show in a room on the second floor of 19 Colonial Avenue, just west of AIC.”

Though it seemed like a match made in sponsor heaven, the connection with Milton Bradley was short-lived. Dismayed but not discouraged, Glendora shopped the show around and the SS Glendora sailed on to General Electric’s WRGB in Schenectady, NY where it ran five days a week before eventually morphing into Satellite Six, with Glendora the captain of a 1950’s-style sci-fi spaceship and running cartoons such as Felix the Cat and Bugs Bunny.

“I finally decided that God was the universe, so to understand the universe, I enrolled at SUNY Buffalo as a graduate student in physics.”

By 1961, videotape began to replace live programming, and in 1962, after four years at WRGB, Glendora was let go from the Schenectady, NY station. Though she made a vow to return to television in 10 years, it was around this time that she underwent what she calls an “inner conversion.” She tried meditation, but found it unsatisfying. She started and ran a volunteer lunch-hour and after-school program for disadvantaged children at the local Methodist Church for several years. “All this time,” she said, “I’m trying to find God. I finally decided that God was the universe, so to understand the universe, I enrolled at SUNY Buffalo as a graduate student in physics.”

Her relentless search for the divine, later influenced by her study of physics, led her to write several volumes: Be Perfect, Here is the Answer to Everything, Love and Physics, and The Glendora Happy Book.

In 1972, Glendora honored her vow to return to television by entering the brand new world of cable. She began her long-running talk show, A Chat With Glendora, at Lackawanna Cable, a tiny station in a suburb of Buffalo, NY with the mission of interviewing ordinary people doing extraordinary things. When Congress passed the law that required cable companies to provide a public access channel and Sony came out with its first “Portapak,” Glendora saw another opportunity. “I presented myself as a public access coordinator and went out and covered all those things that had never been covered before — soccer and basketball games, the bridge clubs, the Y, the churches. The little people were finally getting their coverage.”

By the mid-seventies, Glendora was also a one-woman advertising agency, writing, acting in, and buying airtime for commercials in the New York broadcast market for clients such as the New York/New England McIntosh Apple Institute, New Jersey Peaches, and Worthington Foods. One year, she even persuaded the CEO of MetLife to deliver a Christmas message that she taped and placed during the six o’clock news. At WNEW, she negotiated a segment following the Bill Boggs show, Glendora’s Cheerful Look at the News, continued to produce ads for small businesses, and developed the Careers Unlimited series in which executives talked about their work and gave youngsters advice. In 1987, Glendora appeared as a guest on Late Night with David Letterman, an invitation she says came not long after she interviewed the president of NBC.

In 1994, Glendora sued a Long Island cable company for taking her off the air in violation of the law that states no cable operator can exercise editorial control over public access TV. The court agreed with Glendora and her Chat was restored. “It was a landmark case,” she said. “I went without lawyers, I did it pro se, and I won. The cable companies were shocked. They were so used to getting whatever they wanted, so used to winning, but this time they didn’t. Public access TV is free speech TV, it’s an electronic soapbox, and it cannot be subject to editorial control by a cable company.”

Glendora spent years fighting corruption in the courts, filing hundreds of pro se lawsuits, including one against the powerful international banking family, the Rothschilds. Though she is no longer involved in litigation, she remains a staunch believer in the necessity of a well-informed citizenry as the best defense against violations of constitutional and civil rights.

Today, A Chat With Glendora is still going strong, running every week on 63 stations from Boston to San Diego, including the top 10 markets. You can find her on YouTube, including a 2010 documentary by Victoria Kereszi, as well as on Facebook and Twitter, telling jokes, spreading joy, and sharing her profoundly mystical faith in God’s goodness and nearness.

Glendora shares her home in Nassau Village, New York with her 12-year-old vegan cat, DotCom, and rises before dawn to meditate and read Scripture, write in her journal and sing hymns before calling a long list of people to check on and cheer them. She also hosts the occasional vegan dinner party and keeps her assistant, Madeleine, busy three afternoons a week. Kerrie, a high school senior, stops by to help out, and Austin, a senior at Northeastern University, acts as her digital guru.

When asked what she thinks of the brave new online world, all of the amazing developments in media, Glendora, this earliest and most enthusiastic of “early adopters,” a woman who has known the magic of television from the time it first cast its spell, answers as one might expect from someone who loves life — and reaches out to others — as much as she does: “I am dazzled by the new technology,” she says. “Just dazzled by it.”

Tags: A Chat With Glendora, Abbott and Costello, AIC, American International College, Be Perfect, Bob Hope, Bobby Clark, Boston, Boston Globe, Boston Post, Buffalo Evening News, Bugs Bunny, Cheerful Look at the News, Christian Science Monitor, David Letterman, Dean Martin, documentary, DotCom, Eddie Cantor, Felix the Cat, Franklyn Buell, Here is the Answer to Everything, Jerry Lewis, Lackawanna Cable, Love and Physics, Lucent Magazine, MetLife, Robert Young, San Diego, Satellite Six, Springfield Union, SS Glendora, The Glendora Happy Book, Victoria Kereszi, Worthington Foods